In Bolivia, the Central Bank oversees the payment system.[1] While the Financial System Supervising Authority…

UK’S REGULATORY SANDBOX: KEY TAKEAWAYS FOR BOLIVIA`S BENEFIT

Fernando Landa and Mirko Olmos

Innovation is the cornerstone for any country’s development and competitiveness. There is little to no doubt that finance is the area where innovation has impacted the most throughout the years, and even more during the past decade. The still standing question remains: how can the governmental administration look for staying on top of technological breakthroughs whilst –at the same time– safeguarding both its national interests and those of its population? The United Kingdom has most likely found the answer.

I. The UK’s regulatory sandbox.

Back in 2016, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”) announced the launch of its “regulatory sandbox”, with the purpose of removing unnecessary barriers for banking and finance businesses looking to innovate.[1] To the date of this article, worldwide countries have adopted similar ideas: there are 73 sandboxes in 57 jurisdictions.[2] In South America, only Brazil and Colombia have one.

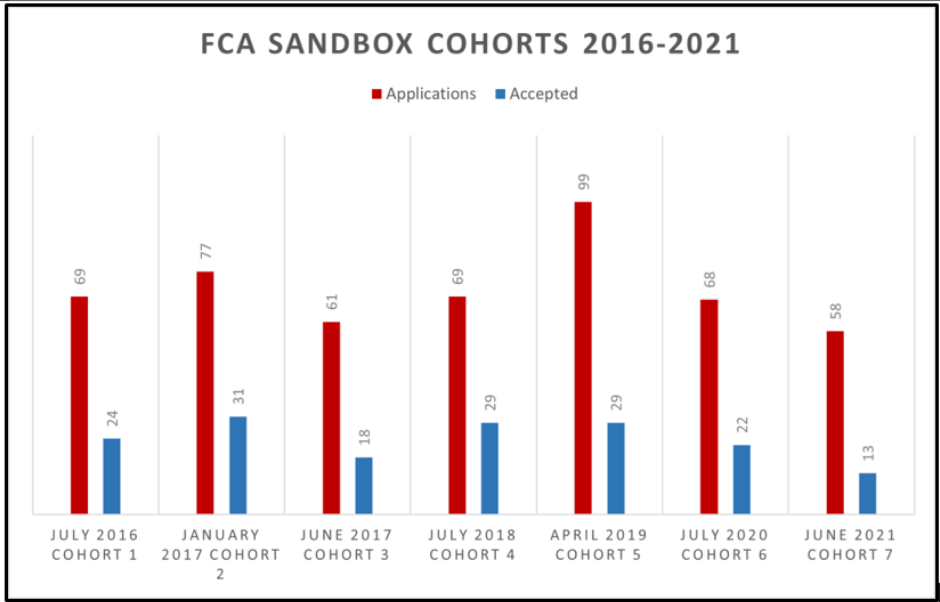

Broadly generalising, a regulatory sandbox is a formal programme where regulators allow market participants to test innovative financial services or new business models in real-life settings.[3] Up until 2021, FCA’s sandbox had 8 cohorts, with just over 500 applications and over 150 firms accepted for testing:[4]

Source: author’s own elaboration based on FCA’s official data. Number of applications and accepted companies to FCA’s Sandbox from 2016 to 2021. Since August 2021, the sandbox has followed an “always open” model.

An author portrays the FCA’s regulation as being data-driven and centred into information gathering, forming expertise, and deploying bespoke regulatory solutions.[5] Other similar countries take a more reserved approach, looking to shape the market with their regulatory powers.[6] Since August 2021, FCA’s Sandbox follows an “always open” regime, where companies can always apply and cohorts as such are no longer a thing.[7]

The change has a reason: in 2020, an independent review of the UK’s FinTech was conducted with the purpose of identifying key areas for better developing the UK’s FinTech sector.[8] One of the recommendations was to enhance the Sandbox by making it available on a rolling basis rather than in time-limited cohorts.[9]

At being open to change and adapting the rules of the Sandbox to the needs of the participant companies, the UK most certainly demonstrates that it is looking towards maintaining its role as the lead country in FinTech initiatives.

Effectively, financial regulation endeavours to strike a balance between protection for the population and innovation to the benefit of the market. The latter ultimately leads to the benefit of the very same population. By implementing the regulatory sandbox, the UK experience seems to elucidate a roadmap to foster financial innovation simultaneously encouraging top-end regulation.

II. What can Bolivia learn from this?

Up until now we have seen that the way financial services are being provided is changing at a hasty pace because of technology breakthroughs among other accelerating factors. The outstanding question is whether Bolivia’s regulatory approach is enough to adapt for what is to come.

In Bolivia, the Financial Sector is regulated and supervised by the Bolivian Central Bank and the Financial System Supervisory Authority (“ASFI”, by its acronym in Spanish). Bolivia’s –already outdated– Law No. 393 of Financial Services (“Law No. 393”) regulates three types of financial entities, (i) State-owned or majority State-owned financial institutions, (ii) Private financial intermediaries, and (iii) complementary financial services companies.[10]

The following complementary financial services companies are directly regulated by Law No. 393 or were introduced to the regulation by ASFI:

- Financial Leasing Companies.

- General bonded warehouses.

- Factoring Companies.

- Clearing and Settlement Houses

- Information Bureaus

- Money and Securities Transport Companies.

- Electronic Card Management Companies.

- Currency Exchanges.

- Mobile Payment Services Companies.

- Money Transfer and Remittance Companies

Whilst these companies can only provide the services determined in the laws and regulations,[11] ASFI retains the faculty to introduce other types of financial services not covered by Law No. 393, as well as financial companies that habitually provide these services.[12]

However, any additional service needs an authorisation from the Bolivian Central Bank and ASFI.

These split-way road between a closed list of complementary financial services as set by law and an inextricable authorisation requirement from two of the most complex Bolivian regulators have become a very effective barrier to innovate in the financial market. In sum, it has led to the current stagnated landscape of financial services.

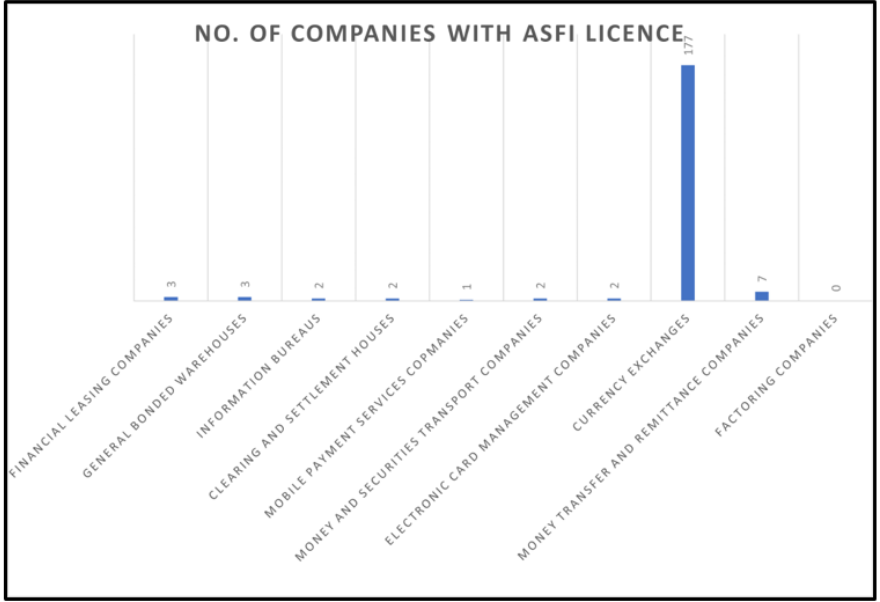

As of 4 April 2022, the number of companies registered before ASFI to provide complementary financial services is as follows:[13]

Source: author’s own elaboration based on ASFI’s official data.

As can be seen from the data above, the number of Currency Exchanges far outweighs the number of any other complementary financial services company. Even if it is considered jointly.

What happens to FinTech companies whose business models do not strictly adhere to the company types determined by Law but create value to society by implementing new models of financial services?

To date, companies and/or individuals lack a clear, direct and formal procedure to request ASFI the review and/or incorporation of the new business model into either an existing type of complementary financial service company, a new type of complementary financial service company, or affirming that certain service can be provided off the scope of regulatory needs.

The inflexibility of law and the lack of alternatives can lead, however, to an avert-innovation financial market as it exists currently, or alternatively to a shadow FinTech market to the detriment of regulation and its goals.

Nevertheless, it is worth remarking that Law No. 393 also empowers ASFI, among other things, to:[14]

- Ensure the solvency of the financial system.

- Guarantee and defend the rights and interests of financial consumers.

- Regulate, exercise, and supervise the internal and external control system of all financial intermediation and complementary financial services activities, including the Central Bank of Bolivia

- Establish preventive control and surveillance systems.

- Authorise the inclusion of other types of financial services and companies providing these services in the scope of regulation.

Provided by law, ASFI is empowered with enough faculties. A Regulatory Sandbox would likely fall within its powers and it would not require further legal authorisation. By introducing one, Bolivia would be taking a step further into making its financial system more inclusive, democratised and with better opportunities both for entrepreneurs and established companies looking to provide bespoke solutions where legacy firms cannot reach, who would benefit from having clearer paths for reaching better results.

Note: The content of this article reflects the opinion of the author only. Nothing contained herein must be considered as either a declaration, acceptance, waiver and/or opinion of Moreno Baldivieso, its partners, associates and/or clients.

[1] Latham & Watkins, ‘World-First Regulatory Sandbox Open for Play in the UK’ (Client Alert – Commentary, 9 May 2016) <https://www.lw.com/thoughtLeadership/LW-world-first-regulatory-sandbox-open-for-play-in-UK>.

[2] ‘Key Data from Regulatory Sandboxes across the Globe’ (World Bank) <https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fintech/brief/key-data-from-regulatory-sandboxes-across-the-globe> accessed 14 April 2022.

[3] ‘Retaining Influence in Post-Brexit International Financial Regulation: Lessons from the UK’s FinTech Framework | Journal of Financial Regulation | Oxford Academic’ 15 <https://academic.oup.com/jfr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jfr/fjac004/6563751> accessed 14 April 2022.

[4] FCA, ‘Regulatory Sandbox Accepted Firms’ (FCA, 8 March 2022) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/regulatory-sandbox/accepted-firms> accessed 14 April 2022.

[5] ‘Retaining Influence in Post-Brexit International Financial Regulation: Lessons from the UK’s FinTech Framework | Journal of Financial Regulation | Oxford Academic’ (n 3) 25.

[6] ibid 6.

[7] ‘Regulatory Sandbox | FCA’ <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/regulatory-sandbox> accessed 17 April 2022.

[8] ‘The Kalifa Review of UK FinTech’ (GOV.UK) <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-kalifa-review-of-uk-fintech> accessed 14 April 2022.

[9] Ron Kalifa OBE, ‘Kalifa Review of UK Fintech’ 108, 35.

[10] ‘Ley de Servicios Financieros 393, Art. 151.I.

[11] ibid, Art. 151.II.

[12] ibid, Art. 19.

[13] ‘Empresas de Servicios Financieros Complementarios’ <https://www.asfi.gob.bo/index.php/esfc-servicios-financieros-complementarios.html> accessed 17 April 2022.

[14] ‘Ley de Servicios Financieros 393, Art. 23.I.